This year we are using quite a bit of curriculum from the Institute for Excellence in Writing. We’re using Primary Arts of Language for Helen’s phonics, Teaching Writing: Structure and Style for Henry’s writing program with our co-op group, and The Phonetic Zoo for Henry’s spelling.

Andrew Pudewa, president of IEW has been a mentor of mine from the beginning of my homeschool career when I saw him speak at the Rocky Mountain Catholic Home Educators Conference. The talk that most inspired me, Teaching Boys & Other Children Who Would Rather Make Forts All Day, is available on his website for a couple of bucks and is totally worth a listen.

There are many things I like about the IEW materials. First, they are all based on reaching auditory learners as well as visual learners. This can be hard to find, particularly in language materials which are often highly visual. Second, the folks at IEW totally get kids – lessons are short, interactive, and based on quick mastery of tiny pieces of information. Pudewa understands that kids want to do what they think they can do, and will often refuse to do anything they think will be too hard.

I have heard others describe IEW materials as “intense” or “parent heavy,” but I think these people may be falling into a common trap of homeschoolers – failing to use the curriculum as a tool and allowing it to be your master. I like the materials because they provide you with a lot of really good material to teach. However, the authors also frequently and insistently encourage you to use the materials as they best suit you and your child. Attempting to cram a lot of information into a passive and even resistant mind is NOT what IEW is about. If it takes you a week to get through a single day’s lesson plan, your child is still greatly benefiting from this high quality material, and you are in no way failing as a homeschooler. Why use subpar material just because the pace is slower? Why not set your own pace using quality tools?

I like Andrew Pudewa and the IEW materials so much, that Pudewa is a household name here. In fact, my son thinks I like him a little too much. During a particularly challenging Phonetic Zoo lesson, my son threw down his headphones and launched into the following tirade.

“This is too hard! I can’t do it! Why do you even like Pudewa so much? You like Pudewa more than you like your own family! You worship him like he’s some sort of god!”

Ahem. I guess I shouldn’t have been so upset when this child chose not to enroll in our enrichment program’s theater class. Clearly, he is already quite skilled in drama.

Fortunately, using some of the skills I’ve learned from Master Pudewa, I was able to navigate this little bump in the road and get us back on track.

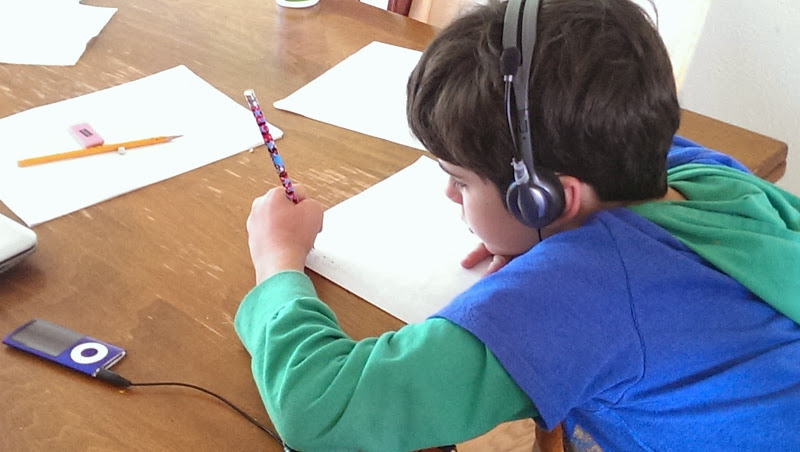

So onto the nitty gritty of the Phonetic Zoo. The program is intended for students beginning in 4th grade and is designed to be self-teaching. It comes with an audio CD that the child listens to for each lesson. Each lesson consists of two audio tracks as well as a large card printed with the lesson’s spelling rule, a list of spelling words, and a picture of an animal or two whose names also illustrate the spelling rule (for example, caiman and ray for the ai/ay lesson).

When the child sits down to do his spelling lesson, he listens to the audio CD with headphones to minimize distractions and to help channel the information directly into his brain. The audio lesson consists the spelling rule repeated every 3-5 words, followed by dictation of the spelling words. The child writes each of the 15 spelling words as they are dictated while also listening repeatedly to the spelling rule. The following track is a self-check with the proper spelling of each word dictated back to the child. The whole thing takes about 10 minutes. As a mastery program, the child repeats the lesson every day until he spells each of the 15 words correctly. This might take one day or a couple of weeks. Once he has mastered the list, he receives a small trading card with a picture of the lesson’s animals on it.

I want to note that these cards are not childish. They have nice line drawings of interesting animals. The program is designed for later elementary kids, and it does not insult them with cartoonish, childish trading cards.

This program has been brilliant for us for three reasons. First, it is something Henry can do entirely on his own. Second, it is short and finite – Henry knows exactly how long it will take and when it’s done, it’s done. This is key for a kid who has trouble focusing on school work. Finally, Henry is a highly auditory learner, so hearing the words spelled back to him is essential. Incidentally, Pudewa asserts that this piece is critical for any type of learner because when we just look at words we don’t really see the order of the letters. You can learn more about the theory behind the program here.

The one bump we hit in the road, the one that prompted the aforementioned accusations of my preternatural adoration of Andrew Pudewa, was caused by my failing to properly introduce the lesson. Henry had done such a good job with lesson one, that I thought I could get away with just throwing lesson two at him with no introduction. While it is a self-teaching program, if your child is a particularly poor speller (as mine is), there are a number of ways you can introduce the lesson to help him succeed. First, you can read through the large lesson card together and have him copy the list of words while saying each letter out loud. Second, you could simply have him listen to the second track of the lesson and write each word as it’s proper spelling is dictated. He could even do this for several days until he is confident enough in his ability to pass the “test.” The point is to learn the material, not to make your kid cry.

While we are only on lesson three (that second lesson took a loooong time to master!) I have seen an improvement in Henry’s spelling, and more importantly, in his confidence around spelling. I really like the self-paced mastery approach because by the time a child can spell the more challenging words, all of the words are solidly cemented in his brain.

I highly recommend this program for anyone teaching spelling, especially if you hate teaching spelling or if your child has struggled with it in the past.