Recently in my homeschool circles, there has been much discussion of when it might be appropriate to push/encourage/nudge our children. How can we discern whether a little encouragement or guidance from us will help them jump to the next level of competence, or push them over the edge of frustration?

Lev Vygotsky, the great educational theorist, posited that there exists what he called the Zone of Proximal Development, or ZPD in the educational jargon. Vygotsky believed that the ZPD is where the greatest learning occurrs. The ZPD is that area of competence just beyond a person’s current level of achievement – a level that one can reach with just a bit of the right help. He called this help “scaffolding.”

Scaffolding is something we all do more or less naturally with babies. Imagine playing on the floor with a baby who is lying on his back and rolling to his side. He’s just about to roll over. He’s almost got it. He just needs a liiiitle encouragement. You hold out a favorite toy just beyond his reach. He reeeeaches for the toy and – woop!- he rolls over. Yay! You’ve just scaffolded rolling over for the baby.

Now notice, if that baby was not yet reaching for toys, or was not yet capable of getting most of the way over on his own, or wasn’t interested in rolling or reaching at that moment, your efforts would have been fruitless.

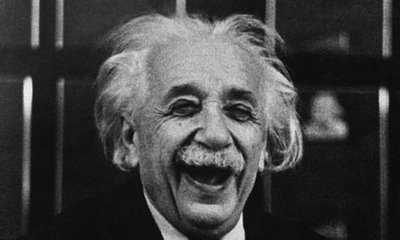

Parents naturally scaffold new walkers. photo credit: sean dreilinger via photo pin cc/caption]

Again, this comes naturally for most of us when we’re working with babies. But it is much less intuitive when we’re working with older children. With older children who have more or less mastered the art of walking and talking, we tend to push a little harder. If a 5 year old can’t write his name, we may feel compelled to put a pen in his hand and use our hand over his hand to walk him through the steps. This isn’t scaffolding. I’m not sure what I would call it, but it isn’t scaffolding.

Our tendency to want to push to this extent comes in large part from a system of schooling that has tricked us into thinking that all kids need to learn the same skills at the same time and at the same rate in order to be at “grade level.” If a 5 year old can’t write his name, he is “behind” and we must push him to “catch up.”

Nah. The problem with this kind of pushing is that it makes learning harder than it has to be. I could start coaching a baby on rolling over from the day he comes home from the hospital, but he’s probably not going to roll over any sooner than if I’d just waited until he was ready. But in the mean time, I may make him think that this rolling over business is a lot of stupid hard work that he’s not really interested in doing.

Okay. So what does scaffolding look like beyond the babyhood? A big question that keeps popping up in my circles, and one I’ve written about before, is teaching writing. I’m not sure why we’re so preoccupied with writing, but it seems that we are. So in my next post I will look at what scaffolding looks like when teaching a kid to write.

One Responses

You know that I've had to deal with a late writer. Beyond his handwriting curriculum which is writing one letter eight times usually, I don't require that he does the writing for any of his other subjects. I do it for him. He is free to do any additional writing he likes and every once in a while he will. I'm pretty happy with our system right now. This winter after he learns to write his lower case letters we'll start doing a bit more writing but it will still be way less than if he was not home schooled. At some point in his childhood he will have the ability and stamina to write but it is not now.